“A senior partner asked to ‘touch my hair’ in order to confirm it was ‘all mine.’”

“An older male colleague interrupted me in a meeting and said, ‘now young lady…’ and then told me how I was incorrect in his opinion.”

“My hearing disability was described in a written evaluation by the board of trustees as ‘making communication difficult for my co-workers.’”

These real examples of microaggressions like these are incredibly common, according to our new research on the subject. Depending who you are, some of them may sound familiar.

Microaggressions—subtle, indirect, and sometimes unintentional acts of prejudice—are a problem that many people (especially in marginalized groups) experience personally, and many others fail to recognize. Because they can be nuanced, we wanted to learn more about the scope of microaggressions and which behaviors people find most offensive.

In partnership with Fortune, We asked 4,275 people about their experience with microaggressions, including overall number of people affected, and how people from underrepresented groups (women, people of color, those with disabilities, etc.) encountered them differently. Sixty-eight percent of Americans say it is a serious problem—and that’s just the start.

Do your employees feel comfortable?

The only way to ensure a truly inclusive work environment is to measure company culture and make positive changes. Our comprehensive guide explains how to do it, step-by-step.

The very real cost of microaggressions in the workplace

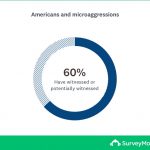

Microaggressions are more widespread than you may think. More than a quarter of Americans (26%) have definitely experienced a microaggression at work, and another 22% are unsure. Thirty-six percent have witnessed one (with another 24% unsure).

With only 40% of workers confident that they’ve never seen a microaggression, there’s a huge population that’s potentially affected—which could also mean bad business.

Seven in ten workers would be upset by one of these disrespectful interactions, and among those who were, half said the action would make them consider leaving their job. Experts estimate that losing a skilled employee costs a company roughly 33% of their annual salary—a high price to pay for some thoughtless words.

What are the most common microaggressions?

Some microaggressions were considered especially upsetting, and close to a quarter of upset workers would leave their job as a result of these issues:

- Unprofessional behavior

- Hearing demeaning comments about peers

- Having one’s idea taken by someone else

Other issues weren’t considered as dire, but were far more common:

Being addressed unprofessionally: Forty-five percent of workers say being addressed unprofessionally would upset them, and nearly three in ten say it would make them consider leaving their job.

Being told “you’re well-spoken” is also common: This issue, while it might seem innocuous, is often an issue for people of color. This is best illustrated through this comment, which was written in:

“When people speak to me over the phone before meeting me, they think I'm white. When meeting me, there is an unintentional facial reaction because I'm black and they are a little shocked. It implies that being black and well spoken isn't the norm.”

29% of workers have experienced it, and the comment is disproportionately upsetting to black workers, with 9% saying it would upset them compared to only 2% of white workers.

Being spoken over: 28% have experienced being spoken over at work—something that women find particularly jarring. (47% say it would upset them compared to 37% of men).

How microaggressions hurt underrepresented groups

Gender, age, physical appearance, and race are the most common identities put down with microaggressions, although experiences run the gamut.

Microaggressions can be incredibly damaging in professional atmospheres. At work, minorities already feel a lesser sense of belonging than their majority peers, and are acutely aware of the conscious and unconscious biases affect their interactions at work.

Microaggressions strain those insecurities, and contribute to a culture where not everyone feels included.

Who is responsible for microaggressions?

Unsurprisingly, only 10% of the respondents believed that they’d personally committed a microaggression, but understanding and taking ownership is important—especially since managers were frequently mentioned as the aggressors in our survey—which is a serious problem, because three in ten workers believe the experience is worse if committed by senior employees.

Microaggressions aren’t always intentional. The best way to address them proactively is through education and awareness.

How employers can address microaggressions—according to their workers

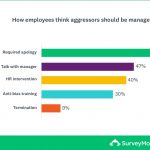

In our recent guide, “How to measure Diversity and Inclusion for a stronger workplace,” Heidi Williams, the CTO of tEQuitable, shared some ways that companies can proactively address microaggressions. To supplement those solutions, we asked respondents about their expectations about punishments for aggressors.

Here’s what the data has to say:

- 67% think the aggressor should be made to apologize

- 47% think managers should talk to their employees about potential microaggressions

- 40% think HR should step in

- 30% think that aggressors should have to undergo anti-bias training (though this goes up to 40% among people who have experienced a microaggression)

- Only 9% think the perpetrator should be fired

And here is Heidi’s initial advice.

- Create psychological safety for addressing these issues without blame. The message should be: “it’s okay to make mistakes as long as you learn from them.” Encourage employees to speak up and build awareness in the moment.

- Introduce education and resources. Share articles and books, create discussion opportunities, role plays, and workshops. Make some trainings required and others optional.

- Lead by example. Recognize and celebrate people who are living your inclusion values. (Only 2 in 10 of our respondents had heard leadership address microaggressions.)

Microaggressions are important to recognize, discuss, and address. That starts with building awareness—getting familiar with the types of statements that sting. To that end, we’ll leave you with a few final examples.

“He would repeatedly refer to something a woman said as ‘girl speak.’”

My boss told me it felt like he was talking to his wife when I asked him for directions to a location.

“A colleague made a comment about 9/11 not realizing my military service during the tragedy and years that followed.”